APIs are hard to use, but they don’t need to be that way.

At ReadMe, we help companies to make their APIs easier to use through documentation. Most of these companies make a product and build an API on the side (“product” companies vs. “API-only“ companies). Since the API is an addition to the product it usually doesn't get too much time. However, just the process of creating docs often takes 3-4 weeks.

No one likes writing documentation. We can make this process of writing both APIs and docs faster by getting to know the user first.

What makes a good API?

The primary purpose of an API is to communicate. APIs communicate through words (docs), code, and eventually data. While the end goal of an API is to share data between products, the first step is to communicate between people. This step is vital. If we don’t excel here, we’ll never get to the data part.

Great APIs don’t leave thinking about this to the docs. It’s the foundation of the API design process.

The best communication comes from being empathetic to the person reading the docs. This means framing things from their point of view. When we see an API from the users' perspective, we can build better tools.

Empathetic APIs

Being empathetic comes from understanding the user, so there’s no N step process that every API can follow. There’s almost always room for improvement.

While there’s no perfect solution, we can look at examples to set a basis for knowing when we're on the right track:

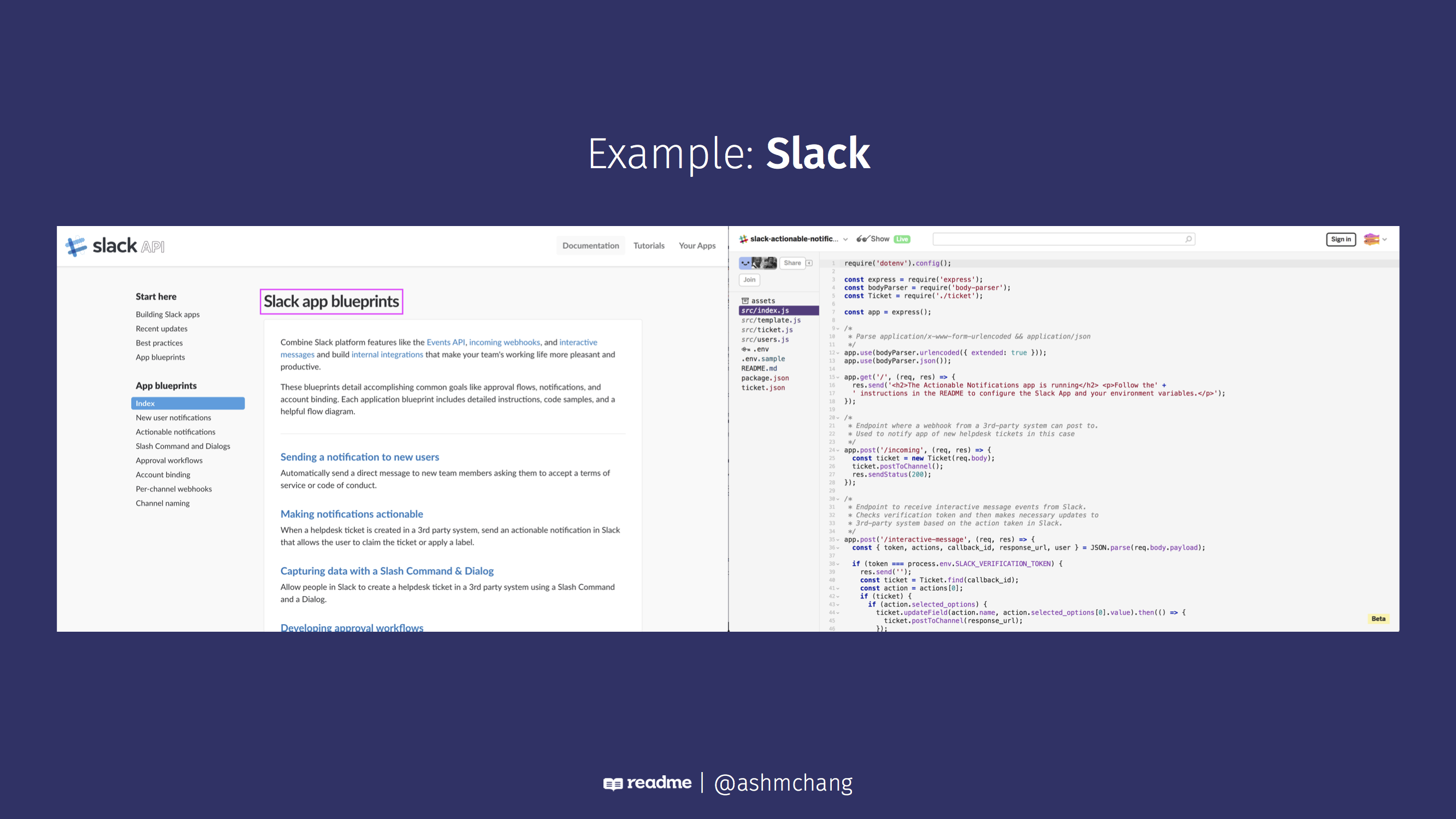

Slack

Slack made empathy for users a priority as they transitioned their product into a platform. They looked at the things people were interested in building on Slack, and came up with seven main “blueprints” to help developers get started. They even added the basic code to Glitch (an app for collaborative coding). This extra step demonstrates their understanding of users. Slack is a collaborative product, and it makes sense that the people building on the platform would feel the same way.

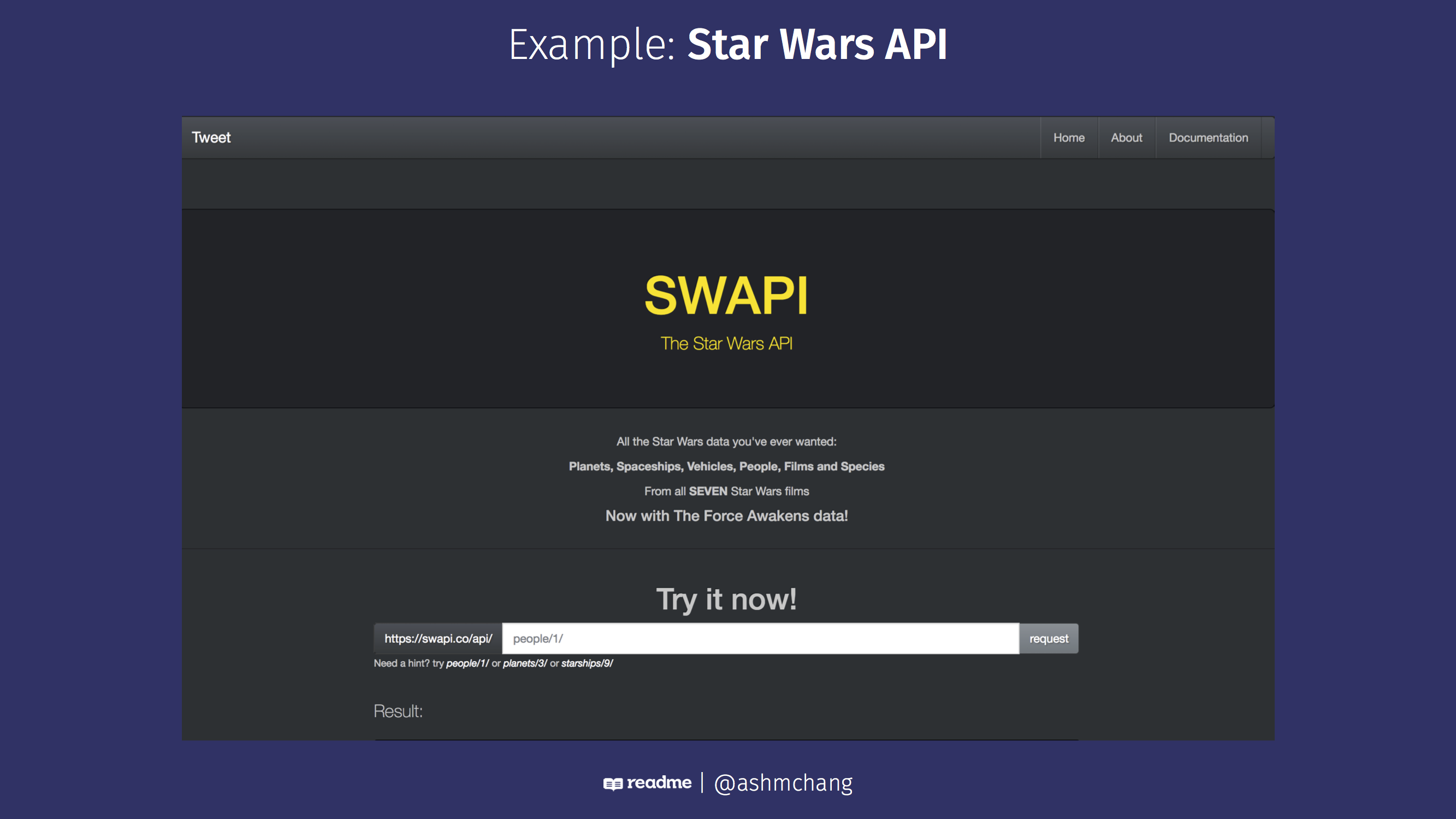

Star Wars API

In a much simpler example, lets look at the Star Wars API (SWAPI). While we often see examples of empathy in docs, the SWAPI demonstrates that real empathy comes before that. The main purpose of this API is to give away data on Star Wars’ planets, spaceships, vehicles, people, films, and species. All that data is free. So rather than making a complicated API, the creators of SWAPI made it as easy to access as possible. There’s no authentication at all. They understood both their user and the purpose of auth in an API, and cut it out.

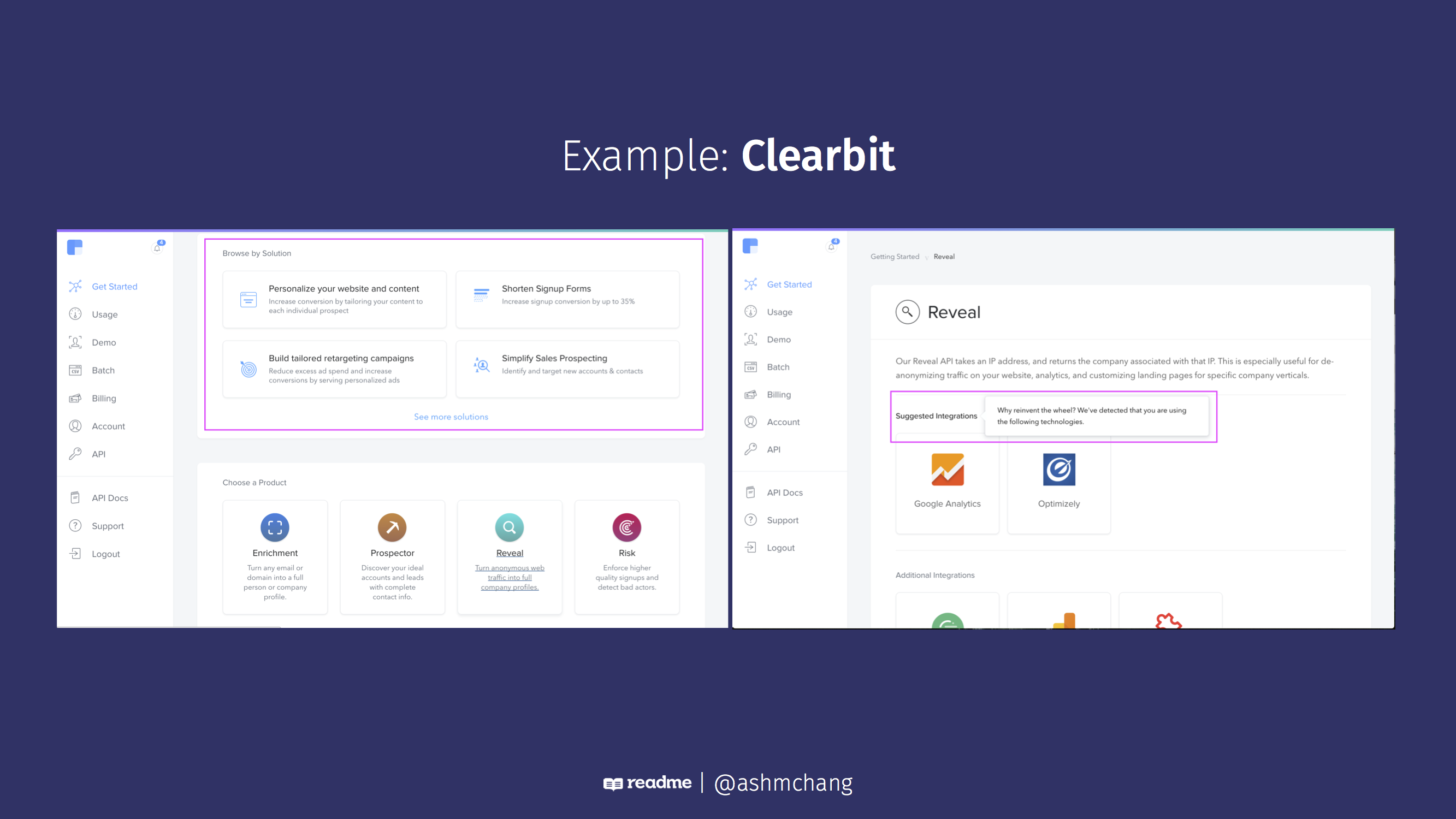

Clearbit

It’s often easier to find examples of companies doing this in the API-only space because they are forced to narrow down the user. On Clearbit’s site, right when a user logs in they offer solution based guides. Even if a user ignores those guides and goes straight to an API, Clearbit understands the use cases of their APIs and are able to suggest possible integrations. This saves the user the mental energy of searching for those integrations. When users can find and try things easily, they’re more likely to use and pay for them.

✨ Magic ✨

When people building an API really understand who’s using it, we get magic. By predicting how people will use things, we can make it unexpectedly easy. This results in something delightful.

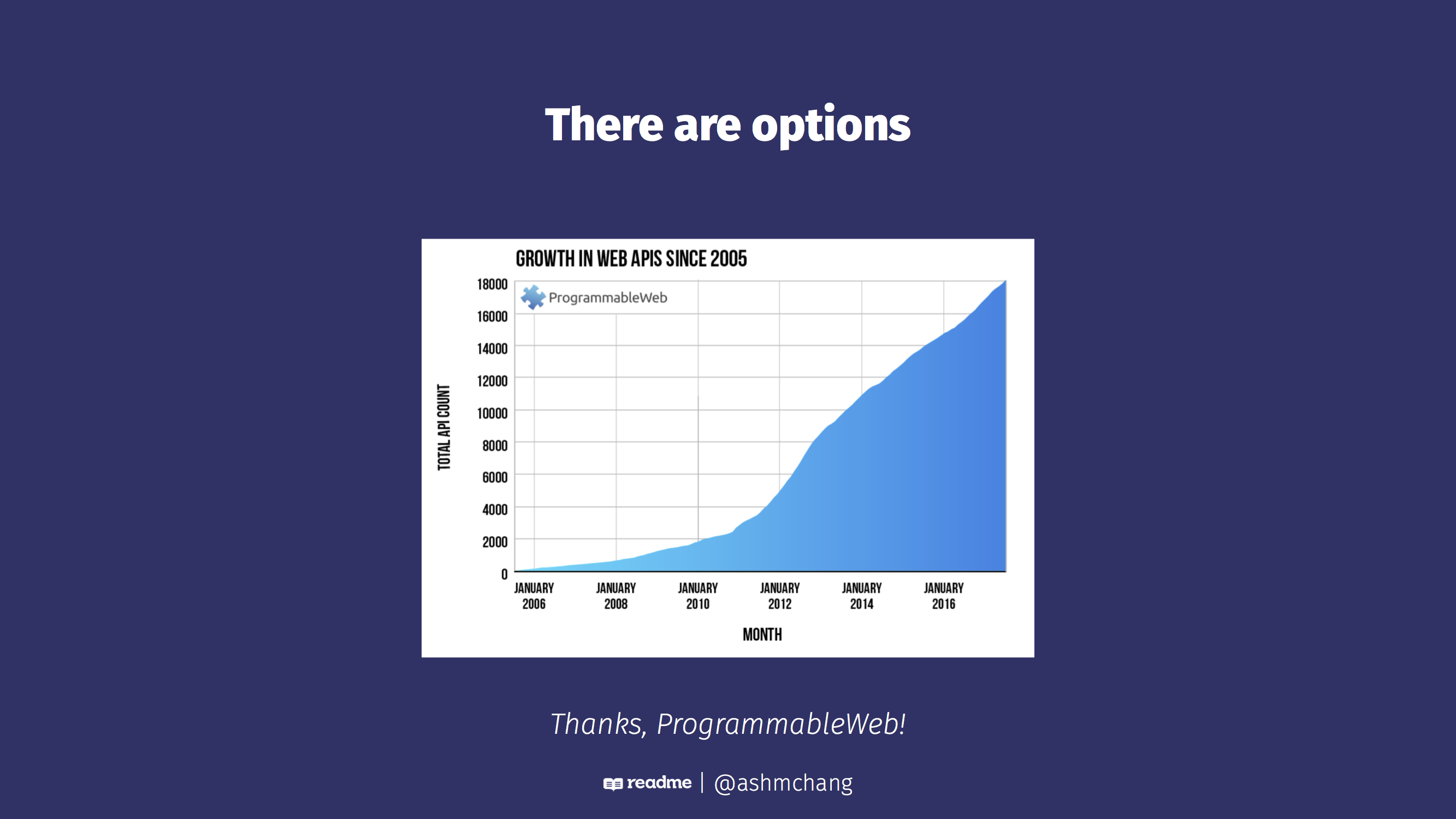

Competition in the API world

The number of APIs has increased exponentially since 2008. It’s easier than ever to create an API. There are often APIs (and products) that provide the same service. Due to this competition, its becoming more important to have an empathetic API and to make it easy to use. We used to say “your docs are your UI”, but more realistically, your API is your UI. People will choose things that are easier to use.

Fixing the API Design Process

A lot of API design is what methods to use or how to make your API modular. Before we make any of those decisions, we need to get to know our user.

The general process for creating an API at a product company looks something like this:

- Users request an API

- Company decides it’s worth engineering time to build an API, but not that much time (product company, remember)

- Company finds the simplest way to expose the necessary endpoints

- Write some docs

- Celebrate! 🎉

In this process, the first thing that companies tend to do is look at their internal architecture. With that perspective, they think about the easiest way to expose endpoints that the users have asked for. This initially looks like an easy win. The early users are getting what they want. Although it may be hard to build on, the company already has a relationship with the users and can explain it to them directly.

Product > API > Users

Problems come in scaling the API. As the number of users on the API increase and their interests increase, it’s just not possible to provide that direct explanation anymore. Engineering time is required to support partners because the API is so complicated that they can’t figure it out themselves. We’re stuck either offering a poor quality API or putting in more resources than intended.

User Centered API Design:

Users > API > Docs

Instead, the first time we build an API the user should be front of mind at the very beginning. Defining our user means thinking about all of the possibilities for how the API could be used, understanding how it aligns with core product strategy, and making conscious decisions about how and why to build it. It doesn’t mean just building the API for the people who asked, and it might mean saying no to them (and other edge cases).

We can see the evolution of APIs towards this point of view with APIs that have been around for a while.

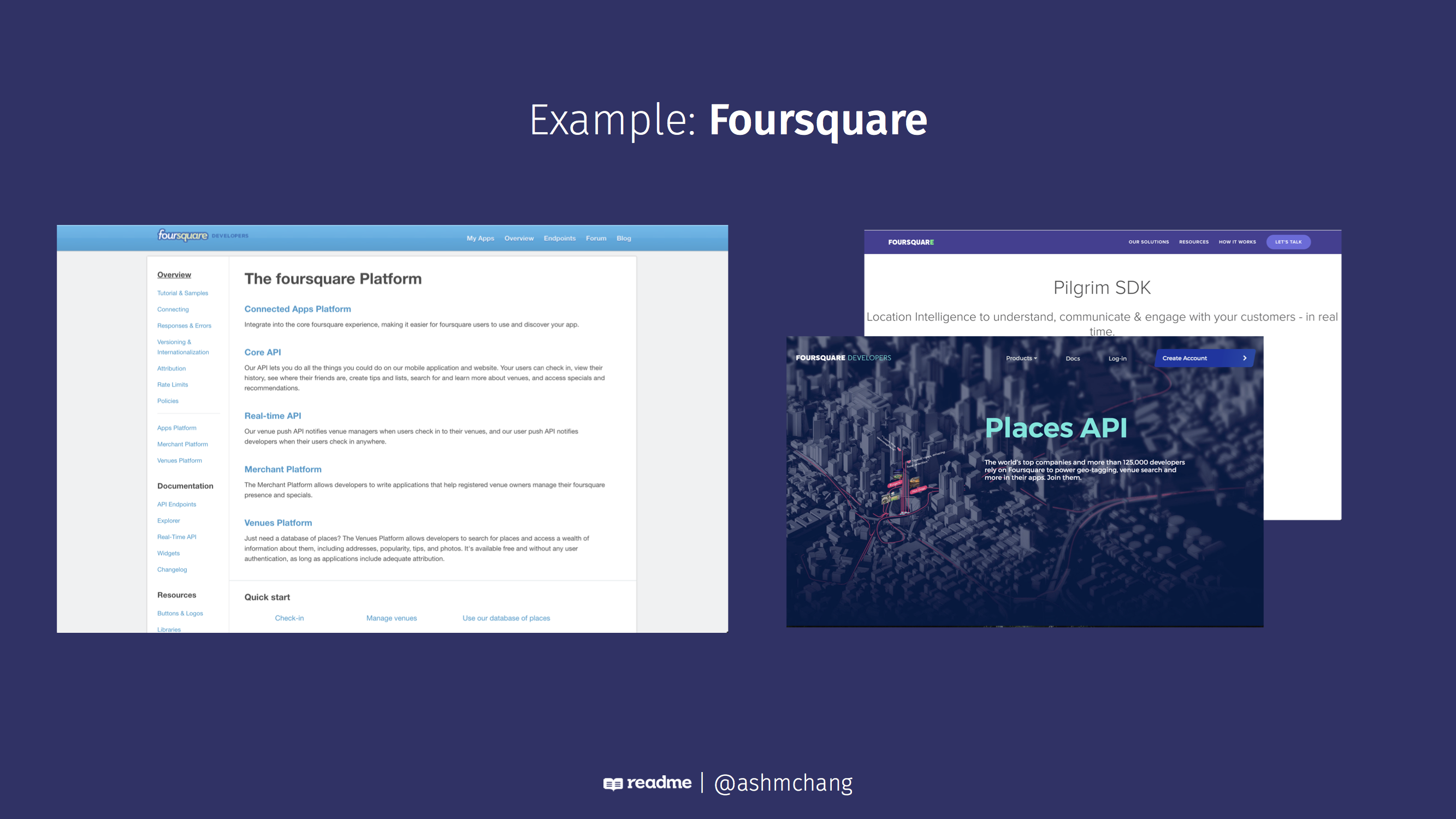

Foursquare’s first iteration of their API focused on what their product could already do. The description of their API literally said, “all of the things you can do on their mobile application”. In the most recent version of their API, they’ve looked at what their data can do for other developers and split up their API by use-case. It’s created a very targeted experience for different types of users. The Places API lets developers do geo-tagging and venue search within their own apps, and the Pilgrim SDK allows companies to understand and engage with customers in real-time as they move through the physical world. Neither does anything near replicating an action in the Foursquare app.

Our new version goes like this:

- Start by getting to know our user

- Expose more endpoints in a way that makes sense for them

- Keep thinking about them in every iteration of the API

We have to make a tradeoff. Rather than just expending minimal effort to pacify user requests early on, we can dedicate more time up front to figuring out what our user really needs. As a result, we’ll spend less time writing docs and supporting users later on, and we’ll create better, more delightful APIs because of it.